Improving My Organization’s Security Posture: A Pentester’s Guidelines

With sophistication of attacks ranging from automated CVE exploitation to state-sponsored, it may be easy to get lost in what should be prioritized from a defensive standpoint. Yet, analyzing the initial access vectors from the hottest advanced persistent threats (APT), when an adversary could successfully get a foothold into your private network by using a Metasploit module, seems ambitious and surely disorganized.

As an internal pentester, I have always found it difficult to stick to the old-fashioned idea that your job ends after a report has been written; however, to be quite frank, I understand it due to the politics that are often induced from stepping outside of your boundaries. Nonetheless, understanding the big picture of the information security initiatives in your organization is extremely valuable, with an input that should help steer the ship in the right direction.

Often, it feels like the Groundhog Day when it comes to prioritization. Either these concepts have to be recalled to various people in an organization due to the lack of singular orientation, or they must be reminded as new information security managers or projects arrive. For these reasons, I have decided to write down some thoughts to solve my own problem, and perhaps to distribute them to whoever deems as relevant.

So, if I want to improve my organization’s security posture, what should I be working on and most importantly, what do I prioritize?

Expectations

This article will address the question of structuring the initiatives of the so-called red, blue and purple teams, and may be seen as scoping into the technical aspects of information security. We will not be looking at the governance of establishing for instance security standards, risk analysis and acceptance, or a security software development life cycle.

However, this does not mean that security governance teams should not be involved in any of this. In fact, they may be responsible for budgets or projects, depending on your organization’s structure, and be your greatest allies to communicate the needs to the upper management.

The Terminology of the Rainbowesque Teams

A few terms will be explained to make sure that no confusion arises, since these sometimes have different definitions.

Red Team

Depending on whom you speak to, this term englobes any offensive security discipline from internal and external pentesting to adversarial simulation. For this reason, I will use the term “Adversarial Simulation” for any initiative that aims, using tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs), to test the detection abilities and responsiveness of an organization. “Red Team” shall be used to allude to a team that works on the offensive side of information security. Note that by “offensive”, I refer to the idea of performing defense by offense, which usually implies finding issues before the adversaries do.

Blue Team

To remain consistent with the above, a “Blue Team” will refer to any area that focuses on the defensive side, from vulnerability management to threat hunting.

Purple Team

Simply put, a “Purple Team” is a collaboration between the aforementioned teams in order to work jointly on the ultimate goal of protecting the organization. An example of exercise is to perform TTPs in absolute transparency, while the defenders build detection use cases.

Disclaimer

I will never claim that this is the sole approach to the question, nor that I have experienced and seen it all. Undoubtedly, the wonderful world of information security is rarely black or white (great, more colors!). Despite this, I believe this article will present a strong strategy that should apply to most organizations that face the problem of securing their and their customer’s information.

Furthermore, some security products will be mentioned to assist solving issues, and I am in no way affiliated with these companies. Also, it must be understood that deploying a tool by itself will practically never solve a problem, unless the dedicated resources possess the proper skill set to operate it and analyze its output.

The Basis

Approaching a problem of such complexity is imposing, to say the least. Fortunately, the information security field includes countless talented individuals who have already pondered upon the question, and generously published their work. It is mostly a matter of finding this information through an ocean of buzzwords and snake oil, along with identifying the truly experienced and successful.

DerbyCon 2018: “Victor or Victim? Strategies for Avoiding an InfoSec Cold War”

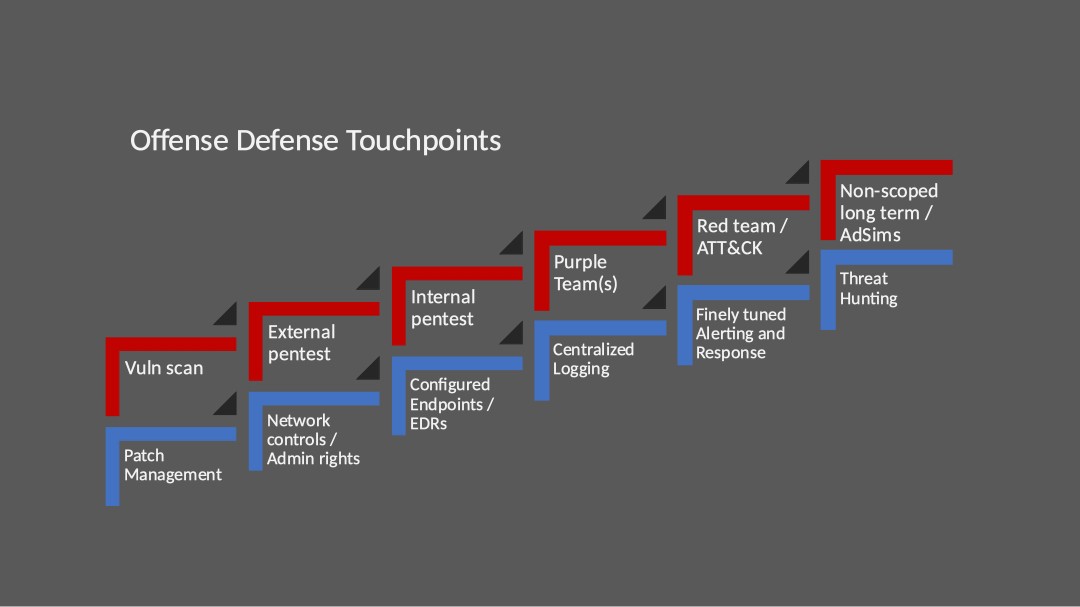

At a first glance, this quality talk given by Jason Lang (@curi0usJack) and Stuart McIntosh (@contra_blueteam) seems to only address the relationship of the red and blue teams, but much more is shared. In fact, a single slide will be the entire basis of this article. I thank them for their great work.

The Slide

The idea shared by Jason and Stuart is simple: both the red and blue teams must climb steps synchronously by implementing these practices, starting from the bottom. This synchronization requires to never lose focus of how the other party is doing, otherwise a complete mismatch of maturity will be induced. Your red team may be eager to perform adversarial simulation engagements but if the blue has just started to deploy an Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) product, you cannot expect them to be able to grow out of the conclusions of your engagements, simply due to not having access to proper tools to monitor the environment.

By laying out clear steps with categories of initiatives, this can be used whether your organization has just started their security program or has been investing into one for quite some time. A team that understands well the current maturity of each of these can quickly identify what needs to be worked on, and most importantly in what order.

The rest of this article will be dedicated to offering a concrete example of how these touchpoints can be shaped for an organization, with hints on how to approach them, as well as how to view the steps in general.

Defining the Rules: When do I climb a Step?

The answer depends entirely on the context of your organization and requires designing your own rules, which are likely to be challenged during each step. By “context”, I refer to internal politics, budgets, technical debt or inventory issues, to name a few. Surely, the experts of your red and blue team must be brought in to be the judges and designers of the said rules.

Any sizeable organization can face issues that increase the improbability of ever completely mastering a category, for reasons out of control of the colored teams. Should the experts be chasing perfection at the expense of going forward? Should they instead channel their creativity and engineer solutions that could perhaps improve the posture, nonetheless?

Remember that fleet of servers which hosts a critical business application and no longer receives security patches due to being out of support? The source code has been lost and the sysadmins have been unable to migrate it to modern servers. Therefore, it will have to be rewritten from scratch, which will take longer than you can afford. This can be seen as a flaw in your patch management process, since you expose an attack surface that cannot be addressed. What if you were to monitor the logs, develop use cases or implement an EDR instead of not going forward because your patch management is flawed? However, do not get me wrong: in no way does monitoring a host and installing an EDR replace the need to install security patches, but it may help you out in the case of a non-sophisticated actor.

Speaking of threat actors, knowing the step that you are at can help identify what degree of sophistication your organization is mature enough to defend against. For instance, patch management and network controls may be successful against an unsophisticated actor. A properly configured EDR and centralized logging would help for a pentester-level actor, who would be seen as performing actions without perfect operations security. Tuned alerting and threat hunting could aim at defending against a nation-state actor. With this in mind, if your organization has started to work on an initiative targeting a sophisticated actor and you know for a fact that an automated attack would be successful, it might be time to reprioritize.

Shaping the Touchpoints

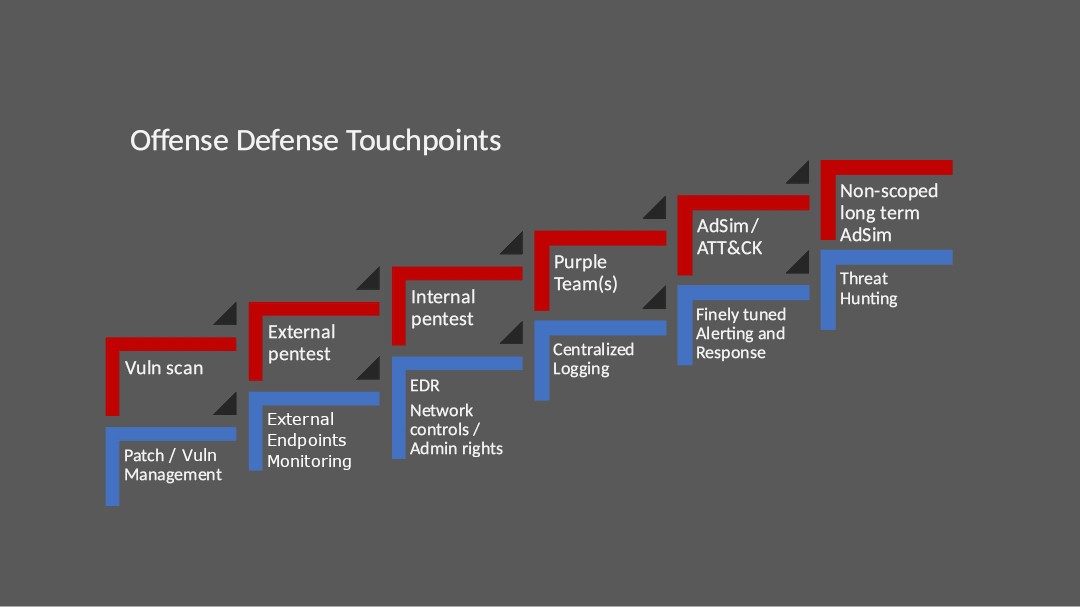

As all organizations should, I have taken the time to analyze the touchpoints and to shape them to match what I believe would be the best for, in this case, a large organization that has publicly accessible endpoints, and will expect to deal with a significant count of vulnerabilities. Most of the steps remain the same, as the original touchpoints already made a lot of sense.

Other than small alterations to reflect the terminology defined above, the “Network controls” category has also been moved a step higher, alongside implementing an EDR. The reasoning behind the changes is the following: any sizeable organization that deals with vulnerabilities will need to implement a vulnerability management process and team, otherwise the likelihood of correcting (if ever) the wave of vulnerabilities found by scanners and the red team in reasonable timeframes is practically nil. Regarding your publicly available endpoints, not monitoring them is a recipe for disaster. All steps will be explained in further details in their respective sections.

Do not hesitate to add more steps, or even to expand the current steps into smaller ones, if judged appropriate.

Now, onto comments and hints regarding each step.

Step One

Vulnerability Scanning

This practice involves implementing an automated scanner into your network to identify vulnerabilities. As the tools are often configured to authenticate on your assets, they can dig into configurations and find out what is not adequate security-wise. In fact, they are good at identifying missing patches, misconfigurations or compliance issues, while the most aggressive web-oriented ones might even find a SQL injection here and there.

Depending on the complexity of your network and number of assets, vulnerability scanning can go from quite easy to implement, to requiring an entire project to manage its deployment. This practice is found at the first step due to the findings usually being the low-hanging fruits.

Quickly, you will be asking yourself countless questions, such as:

- How often should I be scanning?

- Do I really need to scan every single networking asset?

- What about workstations of employees working remotely? (hint: look into agents)

- What are the odds of taking down a critical server? (it happens)

- Who will be responsible of the scanners’ health?

- When and how do I patch my scanners?

- How do I whitelist my tool’s IP address when scanning external assets?

These will need to be discussed and analyzed in great details, and some answers definitely depend on your patching capabilities.

Nowadays, there are countless commercial and non-commercial products, with the former focusing on operating efficiently in large environments. The tools that I have seen the most successfully deployed in corporate environments are Nexpose from Rapid7 and Nessus from Tenable. Much must be taken into consideration when choosing the right tool, such as their ease of integration into your environment, their efficiency and coverage, their reporting abilities, and of course pricing. I highly advise to perform proof of concepts by deploying a few scanners that seem to fulfill your needs, to see how they truly react and what they find. Do not hesitate to deliberately plant vulnerabilities into some systems (non-production in a segregated network, please!) that will be scanned to find out if they will be identified.

No amount of vulnerability scanning will ever replace a pentest but it is not rare to see a pentester perform this activity to quickly identify the most obvious, which could also help orientate their operations.

Do not forget to quickly work on a plan to scan your publicly reachable assets. If your scanner identifies vulnerabilities, it implies that a malicious actor may be able to leverage them.

Now that your tools found vulnerabilities, what’s next? The harsh reality of dealing with scan results will be discussed in the vulnerability management section.

Patch Management

Unfortunately, this step is far from trivial, yet it is the first one on the blue side. I view patching as the foundation of information security, which justifies implementing its management early.

A vendor has worked on a fix for a vulnerability, either self-identified or from an external researcher, and has shared it with its consumers. Now, all that is required is to install it! Definitely easier said than done in environments that have been plagued by legacy systems out of support.

This gets even more complex when a wide range of operating systems (OS) are in use, since they often use different tools to manage patches. Each of your organization’s OS will need to be analyzed to find out what would be the best strategy to patch them, and what product(s) to use.

Then come potential inventory issues which may become the bane of your existence. Your vulnerability scanner might start scanning countless assets that you never knew existed and won’t even know when these can be safely rebooted after patching (when patch application requires it), once introduced into your new patch management tool. This should be taken into account when building your patch management process.

If unable to patch systems for various reasons, a case needs to be built and brought up to management, in order to create new projects. These will often require projects, since it is extremely unlikely that some resources capable of working on a fix will get enough time in their day-to-day responsibilities to work on this, unless scoped in a project.

Vulnerability Management

I have added vulnerability management to the first blue step due to the fact that I have observed countless times in the past that a strong vulnerability management team and process is mandatory as soon as you deal with a large organization. Otherwise, you will find out that a ton of reported vulnerabilities are not going to be fixed any time soon, since there might be no security standard in your organization that requires an asset owner to do so. Even communicating the information to the owners may be a challenge when no team is dedicated to doing so.

Armed with the results of the newly implemented scanner, the vulnerability management team shall unleash a fury capable of causing many nights of insomnia to the CISO. With this imagery, I refer to the impressive count of vulnerabilities that may be reported by your tool. Before anything, the results need to be properly analyzed since these tools tend to be extremely verbose. For instance, you will often find out that a single patch can fix hundreds of vulnerabilities on a host. Also, false positives are very much a possibility.

I have often found myself completely incapable of properly analyzing any results without having access to the scanner’s database where I could perform my own SQL queries. That way, I was able to filter out any noise, and find out what should be addressed first. As an example, I would query for vulnerabilities that are not related to patching due to those being addressed by patch management eventually, which would lead to finding some gems even more critical.

Since vulnerability management is much more than simply looking at scanners’ results, a solid process must be built. This team also needs to know the organization quite well, or at least have a good understanding of the asset owners, which will be confirmed when the pentesting team starts reporting vulnerabilities on many different hosts.

Here are a few questions to help building your process:

- Once reported, how long does an owner have to fix? Is the time length strictly related to criticality?

- What happens when an owner refuses to fix or exceeds the time limit?

- Can the red team document vulnerabilities efficiently or does the process prevents them from doing so?

- How do I handle duplicates? What should I do when a vulnerability is spread on thousands of assets?

- How do I track the status of all these vulnerabilities?

The team also needs to have a good understanding of the vulnerabilities that are reported and their impact. In fact, they must be given the power to reprioritize vulnerabilities once analyzed. Pentesters often get little to no context of the environment where they have found a vulnerability, which can lead to miscalculating the criticality.

It is without a doubt that a tool dedicated to vulnerability management must be implemented, which has to be flexible enough to work with your process. I encourage you to engage into proof of concepts of various options, once your process has been built.

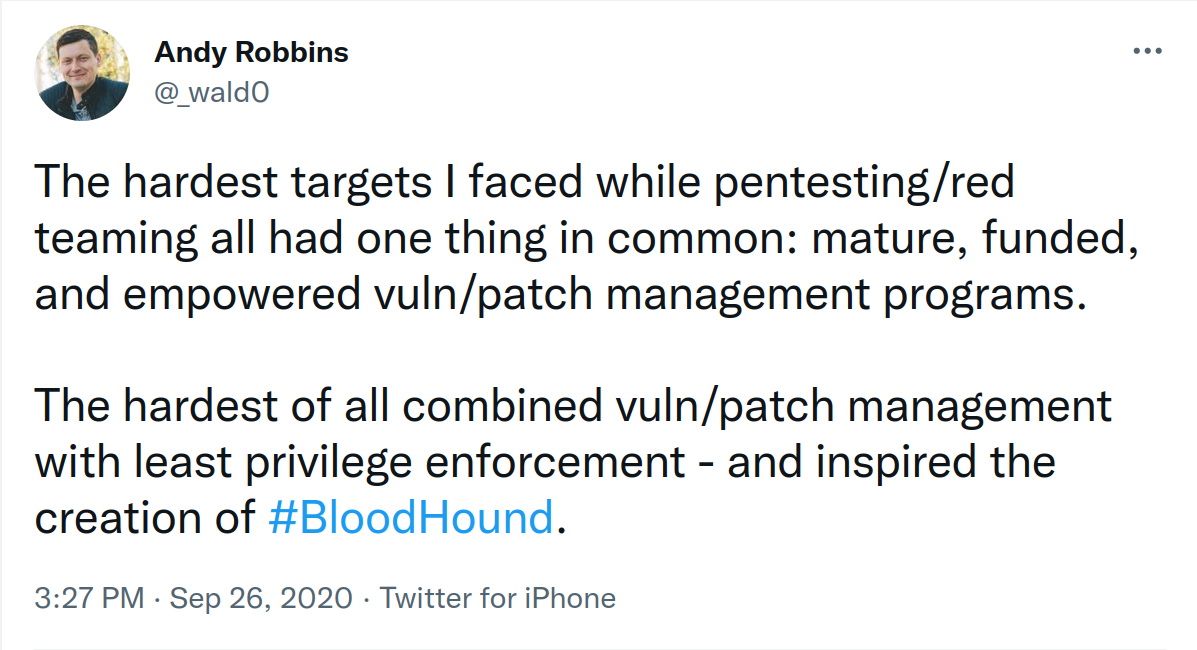

To end this section, here is a wonderful tweet by Andrew Robbins (@_wald0):

Step Two

External Pentesting

This step aims at finding any way of exploiting or harvesting data from outside of an organization’s internal network, under the reasoning that automated tools and actors are constantly scanning for vulnerable assets from the leisure of their basement, which justifies implementing it before internal pentesting.

Your team must ensure to get access to a list of assets that are known to be accessible publicly. When hosting internally, inventories or firewall rules can hand out this information. If unavailable, there are various open-source intelligence tools that can help at the task, such as Amass and Shodan. The use of cloud providers will complexify this, but strategies such as domain/subdomain enumeration (Amass does this) and TLS certificate indexing may work.

Once the targets have been acquired, things become a matter of performing traditional pentesting and harvesting the power of task automation when dealing with a large quantity of assets. Make sure that your pentesters get access to your vulnerability scanning tool so that they can add new targets to scan schedules or view results.

When a vulnerability has been identified, testers must be able to communicate these results quickly and easily, so that your vulnerability management team can start analyzing and prioritize accordingly. Hopefully, your vulnerability management process has already solved this in the previous step.

If your organization does not expose assets publicly, do not view this as a free pass since a lot can be done nonetheless. Here are a few examples:

- What information can be enumerated about the organization? Does an employee leak the entire security product suite on their LinkedIn profile?

- Did a developer commit closed-source code or credentials on GitHub?

- By sifting through data breach databases, can I find an employee’s credentials? Does this employee still use this password somewhere in the organization?

- Can I easily manipulate an employee to run malware through phishing? Will your email filters and protections catch known malware?

- Do email headers leak any valuable information that could be leveraged by a malicious actor?

External Endpoints Monitoring

When the red team conducts external pentesting and successfully exploits vulnerabilities, are their operations being noticed by anyone? If not, does it mean that if an external adversary were to get a foothold on your server, no one would find out?

Under the same train of thought that finding publicly exploitable vulnerabilities should be prioritized over internal ones, it makes sense to monitor your external endpoints first. However, the concept of “internal” vs “external” may seem to blend in when you are under the impression that your internal network is much more likely to be breached through phishing. After all, all it takes is an educated actor and a few clicks from one employee. Because of this, I would not necessarily disagree with the initiative of implementing an EDR first on workstations, or at least work on both at the same time, especially if you have absolute confidence over your external assets’ security (make sure that your pentesters confirm this).

Your monitoring solution can involve installing an EDR (which is also planned for next step but at a larger scale) on your endpoints and/or working on use cases. Despite not having centralized logging yet, forwarding and aggregating these logs in a single console where use cases are developed only for your external assets is crucial. Forwarding is mandatory since it gives you a chance to detect an attacker before they are aware of your logging solution and start altering the local logs.

The current pandemic surely has brought in more appliances exposed publicly, usually for VPN-like features. These will need to be opened up, analyzed and modified to be monitored accordingly. I was surprised while working on Citrix NetScaler’s CVE-2019–19781 to find out that an organization’s web logging retention was 7 hours. This does not help much when you are trying to identify whether a potential breach may have occurred a while ago. And again, if these logs are not forwarded anywhere, how can you confirm their legitimacy?

Step Three

Internal Pentesting

Let us make something clear right away: if you are constantly trying to make your pentesters work in the same conditions as a malicious actor, you will lose. By this, I refer to the thought that pentests must be conducted in a black box way, where the testers don’t have access to source code or a server’s configuration. Reality is that a pentester will have a few days to break into your web application, while an adversary could spend a lifetime. Therefore, your testers will need to work in utter efficiency without having to constantly justify their actions and deal with the occasional “Why would I give you access to the server? Aren’t you supposed to break in?”.

Your organization probably has a role dedicated to something along the lines of guiding projects with an information security-aware advisor. These advisors should be encouraged to request pentests when they have judged them valuable. I would not be surprised if they already have a list of applications or environments that should be tested. Make sure to prioritize according to the attack surface and exposure. If you find out that a new web application built in-house is about to be deployed externally, feel free to catch and test it before it is publicly available.

When it comes to what should be tested first, I like to focus on what is likely to be attempted first by an adversary that would get a foothold into your network. In an Active Directory environment, there are various well-documented techniques which are often successful and, for this reason, very likely to be exploited. You don’t want an actor to get in through phishing, simply launch BloodHound, find out that their compromised user can authenticate with administrative privileges on a server, pivot there, do credential dumping since NTLM authentication is used, get access to a service account and just keep digging into your network that way.

As suggested per the infrastructure case described above, a practice that I find valuable is conducting non-scoped pentests. While highly effective, especially if you encourage your team to work together on a potential chain of exploit, this must be seen as a great privilege and no reckless operations must be attempted (I’m looking at you, ARP spoofers) unless a resource can confirm it cannot have a negative impact. I suggest getting a written approval from your CISO to ensure they are aware of this practice’s existence, and to help out in the case where those spoofers judged it adequate to poison entire subnets.

The External Pentesting section briefly stated the importance of communication with the vulnerability management team. In fact, before the first internal pentest report is written, I highly recommend agreeing on a reporting standard that both teams will be comfortable with. When the structure is the same from report to report, it is much more convenient both for analysis and when a retest is conducted.

Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR)

By itself, a properly configured EDR should fend off unsophisticated actors and definitely annoy any pentester who has not taken the time to work on their tools. This is where the defenders will start seeing operations performed during pentests (on the infrastructure side, that is). Generally, I would say an EDR yields great results monitoring and blocking-wise considering the efforts required to configure and deploy.

Regarding what assets the EDR should be installed on: if there is a system on your network and it is compatible with your solution, go ahead and install your EDR on it. Yes, your development environment also needs to be monitored since they tend to have a lot more than just non-production stuff on there.

As you might already expect, before a large-scale deployment is done, seeing how the EDR behaves into your environment is mandatory especially when it offers features that will block any process that it judges as malicious. It is not entirely impossible that your sysadmins have some funky ways of administrating servers or scripts that could be blocked. Once you are pleased with the configuration, feel free to let your pentesters have a go in case something turns out to be too permissive.

There are two products that I’ve had the chance to experience and see in action. The first of them being CrowdStrike Falcon that offers a feature called Falcon Overwatch, which claims to have a team that performs threat hunting on the logs gathered by the EDR. As a quick anecdote, after performing a privilege escalation on a server that involved running a custom C# reverse shell, this feature eventually raised an alert because the process chain and the network connections between the two subnets were unusual. A pleasant surprise to say the least.

The second product is Microsoft Defender for Endpoint. As opposed to CrowdStrike, this one has a feature called Microsoft Defender for Identity, which has detection capabilities over Active Directory attacks such as kerberoasting, ticket forgery and password spray. However, the conclusion was that it required considerable tuning in order to deal with the false positives.

Network Controls

This section and “Administrative Rights” were moved on par with internal pentesting simply because the pentesters are likely to identify some these in their regular activities. If you are confident you can find these without your pentesting team, feel free to put them back a step before.

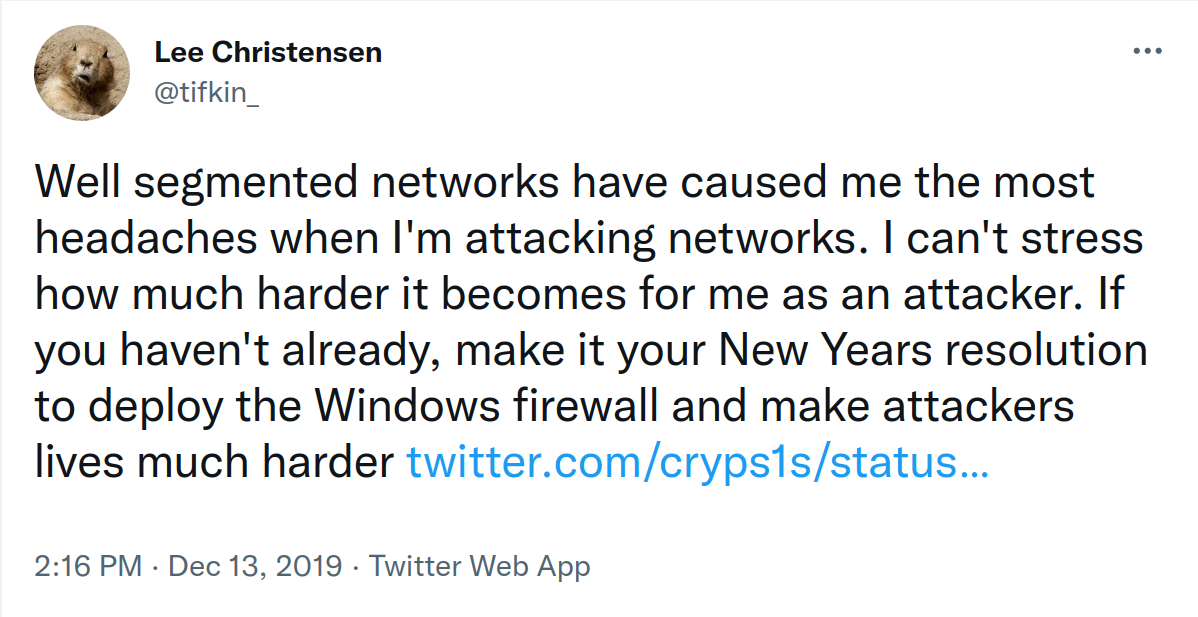

Network controls are a big deal and I will kick this off with one of Lee Christensen’s (@tifkin_) tweet:

How healthy is your network segmentation strategy? Is it a flat network, which implies that your workstations can reach any pot of gold without having to pivot through the network? Is there a magical subnet that makes it possible to reach any other subnets? Not only proper segmentation makes it tough from a technical aspect to move further as explained by Lee, but it also improves the odds that a malicious actor will end up making a mistake and reveal their position in your network. Pair up with network architects and see how your strategy could be improved.

Another initiative could be to look into what vectors can be used to communicate or exfiltrate data to an external command and control server. Is the network configured in a way where as soon as you get on a server, they will gladly initiate HTTP, ICMP or DNS requests egress?

This step also brings in the opportunity to look at your network shares, which many organizations have issues with due to years of misuse. A scan authenticating with your regular, non-privileged domain user should quickly give you an idea of how much sensitive data you can get your hands onto, or even service account credentials that have been left off in a configuration file. Your vulnerability scanner may also have a plugin that reports network shares.

Administrative Rights

An operation that I love to perform when I get into a new environment is to run a quick BloodHound scan in Domain Controller-only mode (so that I don’t become the new hire who starts querying every single computer in the domain). This gives you an idea of what the domain looks like and if it turns out that every single user is a few hops away from DCSync privileges. Depending on how big your domain is, a resource could be dedicated for a while to deleting relationships that turn out to have excessive privileges.

Then, you have the service or sysadmin accounts and how they are used. Can these accounts authenticate on various servers using NTLM, which suddenly provides a way for an actor to pivot if they have access to dumping the lsass process? Or perhaps some sort of UNIX-based equivalent, where password authentication is used through SSH and then any attacker with system call monitoring privileges would get the password in clear text? Limiting your privileges, using Local Administrator Password Solution (LAPS) and public-key authentication can assist solving these.

Last but not least, workstations and servers must be assessed to make sure that they are not vulnerable to trivial privilege escalations. Elevated privileges always unlock new vectors that can be used by an adversary and also act in a stealthier way.

Step Four

Purple Team

To quickly reiterate what has been mentioned in the terminology section, a purple teaming activity is defined by the red and blue team becoming one to solve problems regarding detection and processes.

Since this is where the blue will start forwarding and aggregating logs in a centralized database, the timing is adequate to develop use cases. As more and more logs are available to work with, this is a good opportunity to build your coverage of the TTPs contained in the ATT&CK framework. These have been identified from real-world threats and are therefore techniques that are concretely leveraged by malicious actors. Each of the techniques also mentions in which data sources you can aggregate and build your use case on to detect it.

Both teams must meditate and decide what techniques should be covered first. A good starting point could be to see how to detect techniques typically applied in a domain as described in the internal pentesting section, if the required logs are available. Make sure that you don’t try to catch the most sophisticated actors first. Also, this framework offers matrices built per OS, which you might find useful if you would like to focus on a specific OS first, perhaps the most widely used and more likely to be exploited. Do not overwhelm yourselves with attempting to cover too many techniques in the matrices, as this should be done once your centralized logging is mature.

Once completed, now is the time to perform these TTPs and by looking at the documentation on each technique, see how you can build a use case that would work in your environment, assuming that you do have access to the proper logs.

Other than covering TTPs, any questioning puzzling the blue team can be brought up during this activity to brainstorm an appropriate solution.

Centralized Logging

This is where the architecture of your network and infrastructure in general may come to haunt you. Can your network handle the extra load of forwarding logs at a decent interval? Can your archaic data aggregation tool scale with the influx of logs? Despite these potential issues, this step is mandatory to build detection use cases.

You will be required to build a strategy to collect the logs of various systems in your environment, which are your input for use cases. Precisely what logs need to be collected depends entirely on the TTPs that you desire to detect. For instance, the prioritized techniques that have been pinpointed in the purple teaming exercise will orientate the needed logs. The matrices will also give you a heads up on the following techniques, so that you can plan the collection ahead and fix any issues that may arise.

As a hint, your EDR vendor may be able to provide you a list of TTPs their product covers, which implies that you could build use cases covering other techniques (make sure to validate that your EDR really covers what they say).

Step Five

Adversarial Simulation

Now that we have centralized logging, developed use cases, and are working our way through the ATT&CK matrices, we need to validate how these would be handled if detected in a real-world scenario. Will these techniques be detected and reported properly in the day-to-day operations? How will the analysts respond? Are the response processes well-defined and optimized? Will the investigation stop after the containment of a machine, when the attacker has had enough time to pivot elsewhere? This is what adversarial simulation aims to validate and, as opposed to purple teaming, it happens unknowingly to the analysts and responders.

When establishing the scope and which TTPs should be used, feel free to brainstorm with members of the blue team, as long as they will not be responding to your actions. In fact, you need some of the blues to be aware of the exercise to make sure that, for instance, a critical business server does not get rebuilt if a threat from the exercise is detected on it.

It must be stated that simulating a highly sophisticated actor at this step using TTPs not covered by any use case has little to no value, since the conclusion is already known to the blue team. However, using an unmonitored technique is justified if its entire purpose is to place the operators in a situation where they will be able to perform actions that will test detection mechanisms currently in place. I have also seen the case where the level of sophistication simulated was at the highest, as a last resort to secure funding by proving that your organization can be breached (ah, politics!).

At the conclusion of an engagement, do not hesitate to plan a purple team exercise so that both teams collaborate on solving the identified issues.

Implementing and structuring an adversarial simulation practice in your organization is complex and deserves its own book. Luckily, a great one has already been written by Joe Vest (@joevest) and James Tubberville (@minis_io) named “Red Team Development and Operations”. I highly recommend it.

Finely Tuned Alerting and Response

Other than covering more TTPs, you must ensure at this point to develop impeccable alerting. If your analysts start to ignore a use case because it ends up being a false positive, it must be corrected. Also, this is the step where conclusions of adversarial simulation engagements are analyzed and addressed.

You can also look into your developed cases with members of the red and find out the amount of effort that would be needed to bypass some of these, and adjust accordingly. Is it trivial or would it require complete knowledge of how the detection is built? This could be done in an adversarial simulation engagement or a purple teaming exercise, but feel free to structure this in any way that makes sense, and, most importantly, in the most efficient way.

The information security field is in constant evolution. When it is not a researcher that published their findings, a new APT may act in a clever way that ends up being a blind spot in your detection use cases. Keeping up with these is required when your organization has achieved a level of maturity where it is able to do so.

Step Six

I have not had the chance yet to experience this section in an organization that was truly mature enough to properly implement these. However, these two practices were existent, or at least teams did claim to do precisely that, but since the steps below were not brought up to fruition, they had to spend most of their time working on lower steps.

Non-scoped and Long-term Adversarial Simulation

The highest level of sophistication is simulated in this practice and the idea is the following: without having a specific scope or time limit, your operators will stealthily get multiple footholds in your network, and proceed in the best operations security they can. To avoid getting caught on aggregation, they might decide to let an implant sleep for weeks at a time after performing an action, or even longer if it is planned to be leveraged only in the future.

Then after a while, an implant may be sacrificed knowingly or by mistake. Will the blue team manage to put the pieces of the puzzle together, and perhaps find more implants or reconstruct how this one has gotten access to the system? Will your threat hunting team find your implants in their day-to-day operations?

It is without a doubt that both teams will train each other, either by having the blue share how the red’s operations security was flawed, or how the red managed to remain undetected to the blue. This collaborative relationship is necessary in order to achieve a growth capable of detecting the most sophisticated attacks.

Threat Hunting

Proactivity is a key component to threat hunting. This team will not rely on your built detection use cases and will instead focus on the idea that an actor has managed to breach and not raise any alert. They will still be good consumers of your centralized logs and will build their own queries to analyze the data.

This assumed breach model involves looking for indicators of compromise that have fallen through your detection mechanisms, either by your non-scoped adversarial simulation exercise or an actual threat. In fact, this practice has the best probability of identifying a sophisticated actor that would for instance, compromise your environment through a supply-chain attack using custom malware, and slowly dig through your network in operational security. This would not be caught by your typical use cases and instead requires an extremely knowledgeable resource who understands how these actors operate.

The practice is brought in at the end due to the fact that it relies on the healthiness of the initiatives beforehand, as true for most steps. If your environment is still facing issues that makes it extremely noisy and near impossible to investigate, which allows even the least experienced threat actor to operate in peace, you do not need threat hunting.

To Sum it Up

Experts of both the red and blue team must ensure that they share the same vision on the “what” and “how” of prioritization, and work together to avoid maturity differences. Guidelines are made to do exactly what they say: offer lines of guidance. Therefore, a critical overview of your organization depends entirely on understanding well its context, a mandatory prerequisite to having educated thoughts on how to approach these issues in your environment.

I encourage every organization to fully engage into the exercise of building their own steps of offense defense touchpoints, by collecting input from all the information security professionals.