Capitalizing on BloodHound's Data: Cypher, Object Ownerships and Trusts

BloodHound remains the tool of excellence to assess Active Directory privileges. In most domains that have undergone years of dubious management, only analyzing data gathered from the DCOnly collection method is plenty to keep a fleet of system administrators busy.

While its interface offers built-in Cypher queries, the full potential of the data set is leveraged by crafting answers to your own questions. In fact, relying solely on the built-in queries can lead to missing critical issues.

Why Learning Cypher Is a Must

Before we move on, one must be familiar with the jargon of graph theory in the context of BloodHound:

- A node or object describes an Active Directory object, such as a

User,ComputerandOU. - An edge or relationship links two nodes together. A few examples include

MemberOf,GenericAllandOwns.

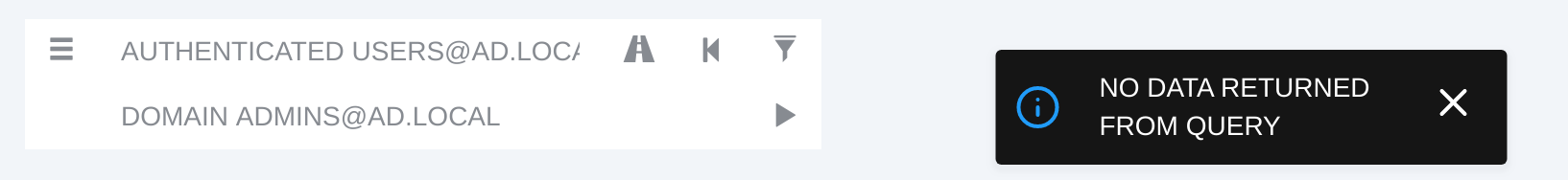

Now, consider the following case where an analyst wants to ensure that no path exists from one of the groups all users are part of, or a special identity that everyone has such as Authenticated Users. In our specifically-generated scenario, by setting Authenticated Users as the starting node and Domain Admins as the ending one, the interface claims that no path exists:

Under the hood, BloodHound executed this query:

MATCH (n:Group {objectid: "$DOMAIN_NAME-S-1-5-11"})

MATCH (m:Group {objectid: "$DOMAIN_SID-512"})

MATCH p=allShortestPaths((n)-[r:MemberOf|HasSession|AdminTo|AllExtendedRights|AddMember|ForceChangePassword|GenericAll|GenericWrite|Owns|WriteDacl|WriteOwner|CanRDP|ExecuteDCOM|AllowedToDelegate|ReadLAPSPassword|Contains|GpLink|AddAllowedToAct|AllowedToAct|SQLAdmin|ReadGMSAPassword|HasSIDHistory|CanPSRemote|AZAddMembers|AZContains|AZContributor|AZGetCertificates|AZGetKeys|AZGetSecrets|AZGlobalAdmin|AZOwns|AZPrivilegedRoleAdmin|AZResetPassword|AZUserAccessAdministrator|AZAppAdmin|AZCloudAppAdmin|AZRunsAs|AZKeyVaultContributor|AddSelf|WriteSPN|AddKeyCredentialLink*1..]->(m))

RETURN p;

What happens if we edit it to include all relationships, simply by removing the filter?

MATCH (n:Group {objectid: "$DOMAIN_NAME-S-1-5-11"})

MATCH (m:Group {objectid: "$DOMAIN_SID-512"})

MATCH p=allShortestPaths((n)-[*1..]->(m))

RETURN p;

The graph then displays that Authenticated Users has the required privileges on the domain to perform DCSync. This is caused by the missing edges GetChanges and GetChangesAll in the built-in query. Since these two are required to get the DCSync privileges, matching on both of them is mandatory to confirm a path. I believe this cannot be done without greatly complicating the query, and explains why this case was omitted.

Custom queries also help to identify the root causes of issues in a domain. An analysis activity that often yields interesting output is to look at object owners, which will be the subject of the rest of this post.

Querying Object Owners

To begin, we must step away from the interface since we will be dealing with a large amount of objects. Also, we are interested in the relationships of the objects, and not their visual representation. Therefore, querying Neo4j’s database directly through the binary cypher-shell is the way to go.

Consider the following query:

MATCH (n)-[:Owns]->(m)

RETURN n.name, labels(n), count(m.name) AS count

ORDER BY count DESC;

To explain it simply, we are matching on any type of object that owns other objects, and aggregating results on the count of objects that are owned. The labels function allows to quickly identify what type of object the owner is.

Analyzing The Results

In this analysis, we aim to validate that no principals may escalate their privileges through their ownerships. Indeed, owning an object implies that you may award yourself any privileges on it, and therefore compromise it. The expected configuration would be to have only highly privileged principals owning objects, such as Domain Admins or Administrators.

| n.name | labels(n) | count |

|---|---|---|

| “DOMAIN ADMINS@AD.LOCAL” | [“Group”, “Base”] | 1955 |

| “SA_IAM@AD.LOCAL” | [“User”, “Base”] | 475 |

| “SA_SUPPORT@AD.LOCAL” | [“User”, “Base”] | 286 |

| “DOMAIN ADMINS@AD2.LOCAL” | [“Group”, “Base”] | 261 |

| “BOBFROMACCOUNTING@AD.LOCAL” | [“User”, “Base”] | 176 |

| “WORKSTATION.AD2.LOCAL” | [“Computer”, “Base”] | 168 |

| “TEST@AD2.LOCAL” | [“User”, “Base”] | 94 |

| “SYSADMIN01@AD.LOCAL” | [“User”, “Base”] | 32 |

| “ADMINISTRATORS@AD2.LOCAL” | [“Group”, “Base”] | 20 |

| “ADMINISTRATORS@AD.LOCAL” | [“Group”, “Base”] | 19 |

Already, some thoughts arise:

- Highly privileged principals do own some objects, but not all.

- The data set contains two domains:

AD.LOCALandAD2.LOCAL. While not reflected here, the built-in query to map domain trustsMATCH p=(n:Domain)-->(m:Domain) RETURN p;reveals a two-way trust, meaning that both domains trust each other for authentication. - There may be some automated process creating objects via service accounts (

SA_IAM@AD.LOCAL,SA_SUPPORT@AD.LOCAL). BOBFROMACCOUNTING@AD.LOCALandTEST2@AD2.LOCALshould probably not own objects.- Any malicious actor with

SYSTEMprivileges on the computerWORKSTATION.AD2.LOCALcan compromise 168 objects. - The system administrator

SYSADMIN01@AD.LOCALmay be creating objects in the Active Directory, resulting in themselves owning them. This may eventually lead to an escalation of privileges, in the case where an object they created is eventually awarded privileges thatSYSADMIN01@AD.LOCALdoes not have.

The aforementioned two-way trust brings in potential for further analysis: principals may have privileges in the opposite domain, and could very well lead to cross-domain ownerships.

Investigating Cross-domain Ownerships

In the database, all objects contain an attribute named domainsid. This helps to quickly identify what domain the object is part of, and is especially useful when investigating cross-domain privileges.

See the following query:

MATCH (n {domainsid: '$DOMAIN_SID2'})-[:Owns]->(m {domainsid: '$DOMAIN_SID1'})

RETURN n.name, labels(n), count(m.name) AS count

ORDER BY count DESC;

Notice that it is nearly identical to the previous one we ran, except we are filtering on domain SIDs. The goal is to get the count of objects AD2.LOCAL owns from AD.LOCAL.

| n.name | labels(n) | count |

|---|---|---|

| “DOMAIN ADMINS@AD2.LOCAL” | [“Group”, “Base”] | 203 |

| “WORKSTATION.AD2.LOCAL” | [“Computer”, “Base”] | 168 |

| “TEST@AD2.LOCAL” | [“User”, “Base”] | 94 |

So, it turns out that WORKSTATION.AD2.LOCAL and TEST@AD2.LOCAL ownerships are only located in the AD.LOCAL domain, while a subset of owned objects by DOMAIN ADMINS@AD2.LOCAL are also there.

Understanding the Impact

At this point, we can scope our analysis on understanding the impact of owning other objects. More precisely, in this example, we will look at paths leading to the compromise of the opposite domain.

Depending on your knowledge of a domain, you might understand the implications of compromising certain principals, even if they do not directly possess the required privileges to compromise the entire domain. Focusing on these key principals is usually as valuable as evaluating the paths to Domain Admins; however, in order to remain configuration agnostic, the next operations will use Domain Admins as the pot of gold, but may be replaced with any key principal.

The next query will be executed in the interface:

MATCH (n {domainsid: '$DOMAIN_SID2'})-[:Owns]->(m)

MATCH p=shortestPath((m)-[*1..]->(:Group {objectid: '$DOMAIN_SID1-512'}))

RETURN p;

MATCH (n {domainsid: '$DOMAIN_SID2'})-[:Owns]->(m)- Matching on all objects of

AD2.LOCALthat own objects from any domain.

- Matching on all objects of

shortestPath((m)-[*1..]->(:Group {objectid: '$DOMAIN_SID1-512'}))- Starting from the

mvariable defined in the previous match, which represents objects owned by objects of domainAD2.LOCAL, we look for any relationship within any amount of hops that leads to theDomain Adminsgroup ofAD.LOCAL. - The path is wrapped in the

shortestPathfunction in order to return only, as it states, the shortest path. This is important, since a query like this in a large domain can be extremely expensive computing-wise.

- Starting from the

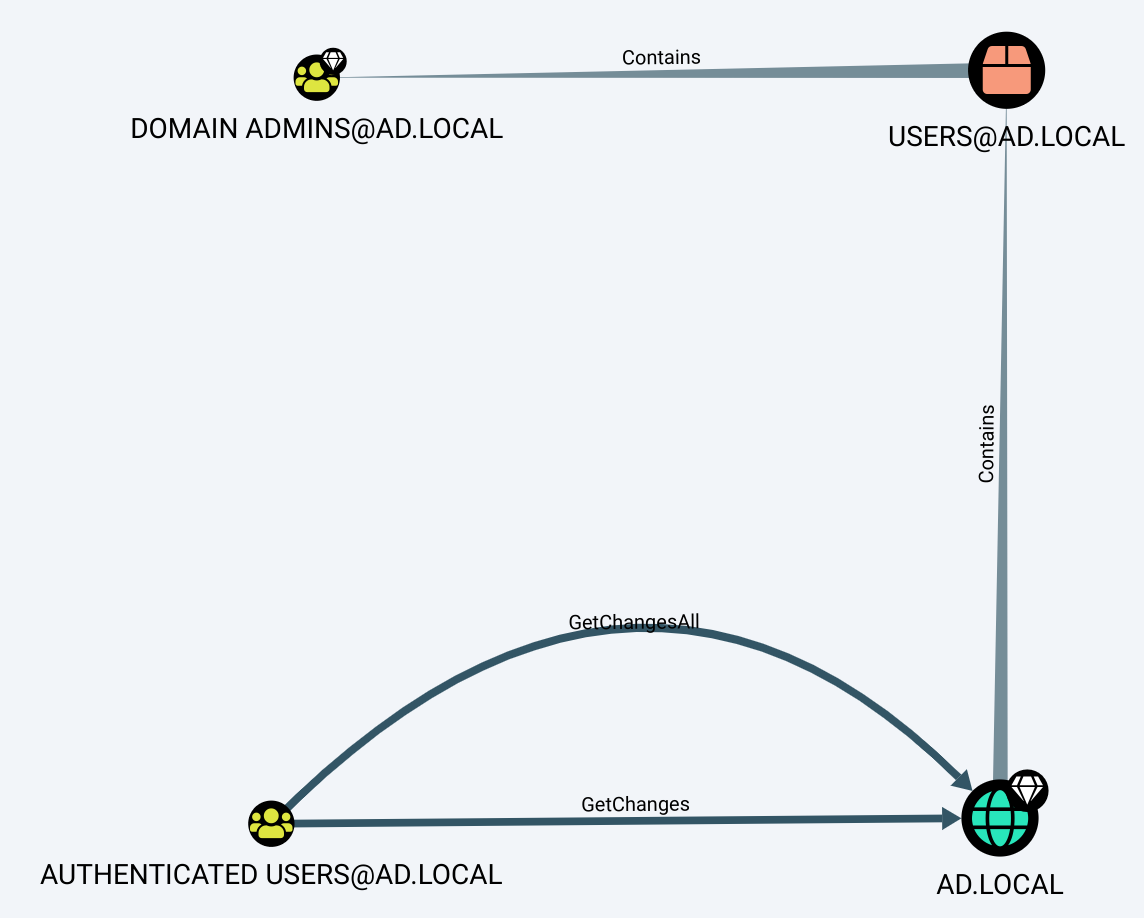

The results signify that some currently unknown object from AD2.LOCAL owns the group BE-199-DISTLIST1@AD.LOCAL that has a path to DOMAIN ADMINS@AD.LOCAL through the ForceChangePassword edge. Fortunately, we already know the recipe to query who the owner is:

MATCH (n)-[:Owns]->(m {name: 'BE-199-DISTLIST1@AD.LOCAL'})

RETURN n.name;

| n.name |

|---|

| “WORKSTATION.AD2.LOCAL” |

At this point, we must further investigate who else has control of the computer object WORKSTATION.AD2.LOCAL within the same domain, but will be left out of this exercise; though, it is already concluded that a domain administrator of AD2.LOCAL is a few hops away from administrative privileges in AD.LOCAL, by hijacking the computer object.

More Cross-domain Fun

Throughout this example, we focused on a single direction to assess privileges (from AD2.LOCAL to AD.LOCAL), but remember that we are dealing with a two-way trust. What if an object from AD.LOCAL can compromise WORKSTATION.AD2.LOCAL? This would yield a path starting from AD.LOCAL to compromise an object of AD2.LOCAL, and then use those privileges to become a domain administrator of AD.LOCAL.

We can query all objects from AD.LOCAL that have direct privileges on WORKSTATION.AD2.LOCAL like so:

MATCH (n {domainsid: '$DOMAIN_SID1'})-->(m {name: 'WORKSTATION.AD2.LOCAL'})

RETURN n.name;

Make sure to query for only one hop, since this avoids the case where objects with indirect privileges are shown.

| n.name |

|---|

| “TAMERA_ARNOLD@AD.LOCAL” |

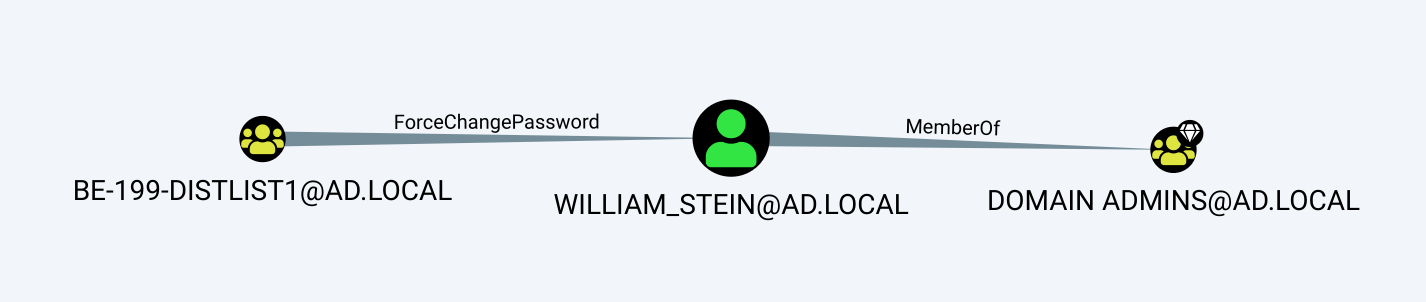

There we have it, TAMERA_ARNOLD@AD.LOCAL has a path to DOMAIN ADMINS@AD.LOCAL by compromising WORKSTATION.AD2.LOCAL. This can be seen in the graph, simply by setting TAMERA_ARNOLD@AD.LOCAL as the starting node, and DOMAIN ADMINS@AD.LOCAL as the ending one:

TAMERA_ARNOLD@AD.LOCAL has GenericWrite over the computer object, and therefore can compromise it through resource-based constrained delegation.

Reporting

Now that we have some findings, we must properly document them to ensure a successful remediation. This step is as critical as the assessment activity itself; what is the point of observing issues if we do not report them adequately?

Despite needing to understand the inner workings of how an Active Directory is configured to be able to tell if some object ownerships are abusive or not, for instance the IAM service account owning objects, it is more than adequate to document your theories, or at least observations so that administrators can confirm if they are intended or not.

In this scenario, I would document the following:

- All paths leading to domain compromise from objects that should not have any privileges.

- Suspicious ownerships, even if they do not currently lead to further escalations, e.g.

BOBFROMACCOUNTING@AD.LOCAL,TEST@AD2.LOCALandSYSADMIN01@AD.LOCAL. - A CSV file containing all ownerships, unless the file would end up being ridiculously large.

We can easily generate this by slightly altering our first ownership query to include the object SID:

MATCH (n)-[:Owns]->(m)

RETURN n.name AS Owner, n.objectid AS `Owner SID`, m.name AS `Owned Object`, m.objectid AS `Owned Object SID`

Then, we can use the procedure apoc.export.csv.query to directly export the output in a CSV file, which will be located under /var/lib/neo4j/import/ on Ubuntu:

WITH "MATCH (n)-[:Owns]->(m) RETURN n.name AS Owner, n.objectid AS `Owner SID`, m.name AS `Owned Object`, m.objectid AS `Owned Object SID`" AS query

CALL apoc.export.csv.query(query, "ownerships.csv", {})

YIELD file, source, format, nodes, relationships, properties, time, rows, batchSize, batches, done, data

RETURN file, source, format, nodes, relationships, properties, time, rows, batchSize, batches, done, data;

Note that the procedure is not installed by default. Refer to this article for installation.

You may also write a query to avoid exporting objects owned by highly privileged principals such as Domain Admins, unless they are located in a different domain. This would greatly reduce the potential noise in the export.

Conclusion

In this post, we experimented with a methodology to investigate object ownerships across domains. By harvesting the power of custom Cypher queries, the data set is manipulated to scope on specific issues, then reused to extract information to help the remediation.

I hope this will convince you that using Cypher during a BloodHound assessment is mandatory, and will inspire you to develop a technique to investigate more scenarios.